The admirably prolific Sarah Hoyt has something to say about writing and the “Muse” canard:

My writing career (though it was 10 years before I sold a story) could be said to have started the night my husband told me writers write every day. He's a musician you see. (Not for a living. He's a mathematician, but the two afflictions often go together.) Musicians practice every day. I told him I wasn't even sure that I could write commercially in another language (this was the year I moved to the US). And I might never have been good enough, and besides, well… besides, I really couldn't force myself to write when I wasn't inspired. He looked at me like I had two heads and told me, no, if I wanted to be a writer I had to write every day. Practice has a magic of its own. Just write it....

The second thing I can tell you is that the muse or inspiration is a lie. Sure, sometimes it strikes and you write stuff in white-hot joy. That's great. But you know what? You can do it when it doesn't strike too.

Sarah’s observations are worthwhile, but I must add a caveat.

Yes, writers write. Yes, writing every day is a salubrious way to defeat your hesitance and develop the “habit” of writing that a productive writer would need. But there is a price, and it can appear rather stiff to the aspirant who’s unprepared for it.

Some of what you write will be bad. Embarrassingly bad. The day after you’ve written it, it will assault your eyes and rattle your brain. You’ll cringe away from it, desperate to believe that you had absolutely nothing to do with its creation, that some evil entity stole your graceful, piercing prose and substituted a deformed mutant changeling. You’ll be tempted to swear off writing forever.

And there is nothing to do for it but to plow onward.

In one of his books on writing, Lawrence Block relates a tale about a writer friend who’d contracted to write the libretto for an opera. The friend called Block in a panic. He couldn’t do it. He couldn’t catch the rhythm of the thing. The story failed to energize him. Every sentence he wrote frankly stank. But he was under contract, and the deadline was nearing.

Block gave his friend this bit of entirely unexpected advice: “Then write a bad libretto.” And the friend took it.

Sometimes there’s no way out. But he who perseveres might find a way through.

A favorite subject of mine, when conversing with other indie writers, is methods of promotion. I’ve learned a fair amount from such conversations. However, I’ve also noticed that very few fiction writers put much effort into their promotional blurbs. It’s a skill that’s worth refining.

Terry Lacy recommends an approach:

Archaeologist Indiana Jones has to get the Ark of the Covenant before the Nazis. He wins the treasure and the girl.

Twenty-one words. The concept is simple enough and one of the many assignments I had to master in grad school. It's based on the simple idea that—according to some psychological study somewhere—if you meet a stranger, you have twenty-one words to get them interested in your idea. That's whatever you're selling, and we're all selling something, from an insurance policy to a novel I want you to read, to a pleasant conversation in an airport lounge, it's all one big sales pitch. If you hook them in 21 words, they continue to listen. If you don't, they tune you out—their minds go elsewhere.

Now before you decide this is stupid, think about it. It's the elevator pitch, only shorter. You don't have an entire elevator ride—you have a sentence—maybe two—before your audience decides if you are worth their time. If that sounds mean, it's a mean old world out there—and in the faceless world of the internet, it's only getting worse.

This exercise is valuable for more than one reason. Obviously, a concise, well-focused “elevator pitch” is useful in approaching busy Hollywood executives. But beyond that, it respects one of the ugly facts of fiction marketing: the potential purchaser won’t spend more than about 60 seconds on his decision to buy or not to buy. And if old Will will forgive me, that is the question, isn’t it?

And, entirely apart from promotional considerations, practicing “precision writing” — producing a coherent narrative in a fixed number of words – is excellent exercise for cultivating the habit of precision in all modes of expression, including oral communication.

Allow me a brief vignette. A few years ago, a young colleague, more or less out of the blue, complimented me on my “clarity,” both spoken and written. He asked how I’d learned it and whether he could make use of the same technique. It gave me pause for thought.

After a moment’s reflection, I said “Meetings.”

“Huh?” he said. “How did that come out of meetings? At the meetings I’ve had to attend, people drone on and on and seldom if ever make a point!”

“Exactly,” I replied. “They horrified me. I became so determined not to be profligate with others’ time that I concentrated on boiling down what I have to say to the irreducible minimum. It turns out that that doesn’t just shorten your meetings; it makes your statements clearer as well.”

And he smiled.

In recent years I’ve become easily irritated by caricatures. Until recently, it hadn’t occurred to me how easy it is to create caricatures among one’s Supporting Cast characters. Some are more irritating than others – the greedy businessman who worships profit and will trample anyone who stands between it and him; the brain-dead housewife who knows nothing beyond Kinder, Kirche, und Kuche; the “crusader” whose motives are pure as the driven snow and whose policies never evoke a second-order effect – but there are many kinds, and all of them are detrimental to the plausibility of a story. The consequences are worse than the typical indie writer thinks.

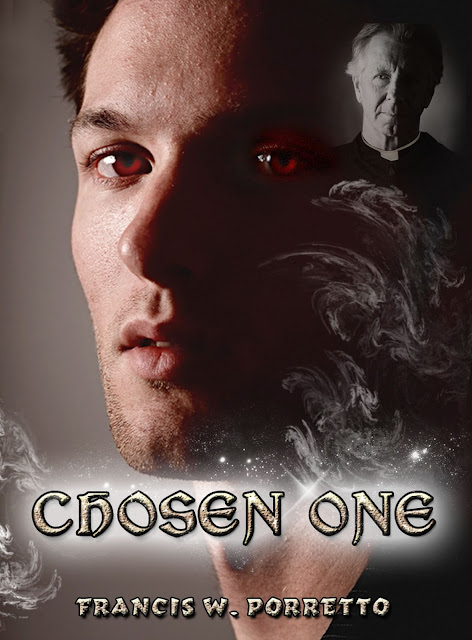

Lately the one that’s acted on my nerves like grade 0 sandpaper is the hyperzealous, utterly intolerant Christian cleric who wants his flock to get out there and fight “sin” (as he defines it) physically. Such stick-figure caricatures of priests and ministers appear regularly in fiction about persons from some “oppressed” minority. The use of such a character as a major antagonist can destroy an otherwise worthy story, entirely because of his implausibility.

(Yeah, yeah, I know: Westboro Baptist Church. Now name another one.)

A good story does require some sort of tension or conflict, but if the tension or conflict arises solely because of a caricature antagonist, it won’t persuade. It will work serious damage on the reader’s “willing suspension of disbelief,” the asset which above all others the writer must strain to preserve. Without that – the acceptance of the “story universe” and its premises as true enough for the purposes of the entertainment offered – the story becomes trite. Cartoonish.

If you’re laboring over a fiction that depends upon such an antagonist, I sincerely and solemnly urge you to reconsider. Your “story universe” already has two strikes against it. You can do better, and you should.

That’s all for today, I think. To those who’ve written to inquire about the status of Experienced, I’m still at work on it...and it’s a lot more work, of more kinds, than I’d expected it to be. I’ve already thrown out two false starts and am straining to develop a third approach wholly divergent from the others. But never fear: it will be finished. I just hope it won’t finish me.

Enjoy your weekend.